Over the last twenty-five

years search engines like Google and social networking platforms like

Facebook and Twitter have reshaped the world. Commerce, education, journalism

and social movements depend on them, and so does Democracy. As we

consider what regulation and oversight need to be imposed on internet service

providers and big media companies, we must look at what they actually do. China

is a good case to consider.

The repressive Chinese

government uses censorship and intimidation as methods of controlling political

dissent. While many Americans probably consider that to be anti-democratic and

authoritarian, they might concede that the Chinese government is entitled to

enforce its own laws within its borders. A question arises when private, for

profit corporations, which are not Chinese, do that government’s dirty work for

them.

One case to consider is that

of Professor Guo Quan, a Chinese National who dared speak against his

government, even going so far as to found an opposition political party, the

New People’s Party.

According to February 2008 article by Jane McCartney from the Times in Beijing, Professor Quan’s name was blocked from searches on Yahoo and Google. Quan’s answer was to file a civil suit against them in US court stating, “They have violated my political rights. I am opposed to violence and dictatorship but these sites have blocked me….To make money, Google has become a servile Pekinese dog wagging its tail at the heels of the Chinese government.” Unfortunately, Professor Quan was arrested for ‘subversion of state power,’ and is presently serving a 10 year prison sentence. Here’s the progression of events:

According to February 2008 article by Jane McCartney from the Times in Beijing, Professor Quan’s name was blocked from searches on Yahoo and Google. Quan’s answer was to file a civil suit against them in US court stating, “They have violated my political rights. I am opposed to violence and dictatorship but these sites have blocked me….To make money, Google has become a servile Pekinese dog wagging its tail at the heels of the Chinese government.” Unfortunately, Professor Quan was arrested for ‘subversion of state power,’ and is presently serving a 10 year prison sentence. Here’s the progression of events:

Quan criticizes his governmentà His government gets Google and Yahoo to delete

him from the public recordà Quan

sues Google and Yahooà His

government throws him in prison for a decade.

So why should this matter to

Americans? Six months ago I might have thought such a scenario was highly

unlikely in the US. It’s amazing how quickly circumstances can change.

Free speech

is fundamental to democracy. A century ago the US Postal

Service kept us connected. With the advent of radio and TV the US

government declared the airwaves a public trust. The infrastructure of

our communication system is the platform of our social discourse, and as

such should be: state of the art, accessible to all and owned by

the citizens.

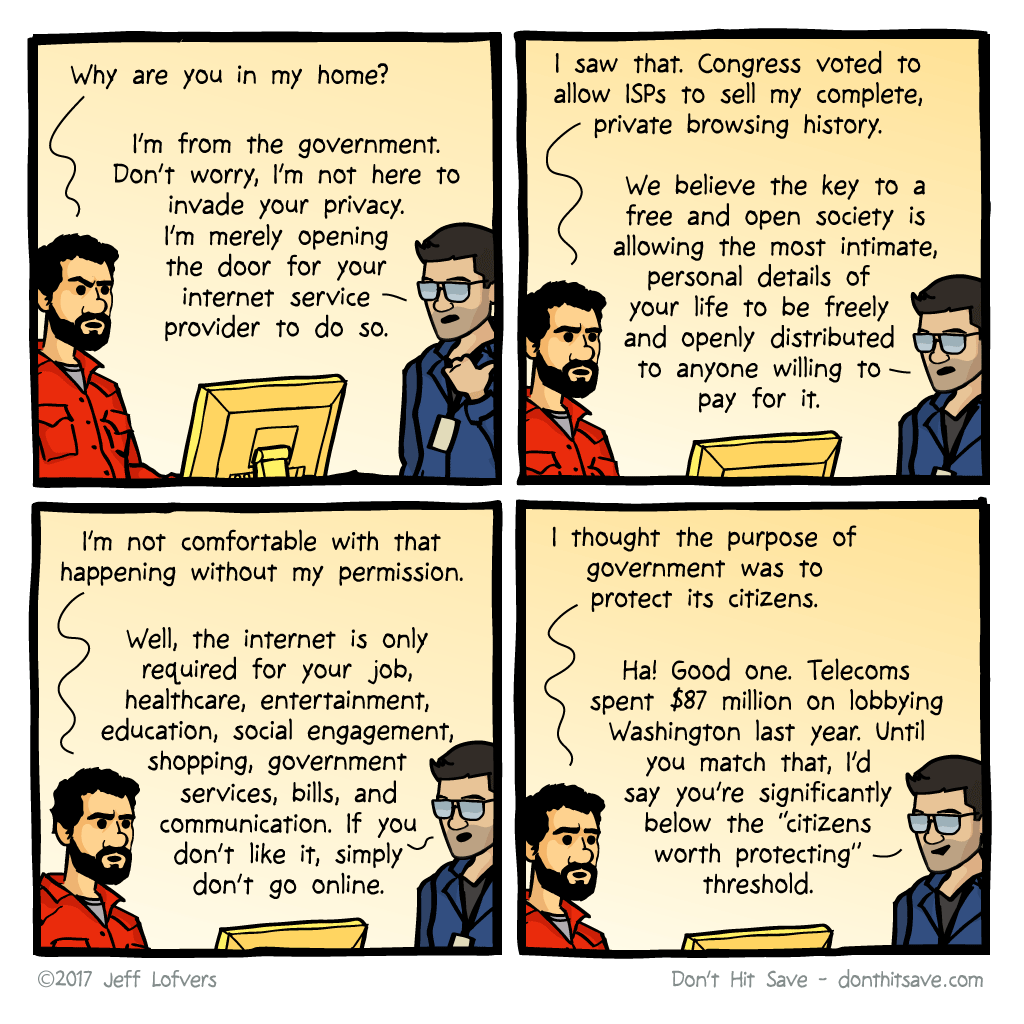

Things that the US government

cannot do, whether because they are illegal or politically undesirable,

might be done by private corporate persons acting on the government’s behalf.

This is extremely troubling for a number of reasons. It creates opportunities for

collusion between corrupt or authoritarian government and corporations

seeking to extend profits. What's more dangerous, and far less

understood, is that when an industry is first coming to

market their practices, the consumer's expectations and

models for that business- government interaction are not yet defined.

With few rigid guidelines in place, practices which serve the corporation

or are useful to the government usually become codified as

standards for the emerging industry. Historically when this happens the independent media alerts the citizens of abuse or collusion, inspiring the citizens to

demand reform and regulation for the industry by their government. When

the industry in question is the media, or the information

infrastructure itself, we must be especially diligent.

On January 17, 2012 Rebecca MacKinnon, author of, Consent of the Networked: TheWorldwide Struggle for Internet Freedom, was interviewed by Democracy Now.

She had this to say, “If we want democracy to survive in the internet age, we really need to work to make sure that the internet evolves in a manner that is compatible with democracy." MacKinnon points to the insidious nature of the state’s use of the private sector to conduct its surveillance or censor its people’s social discourse. We in the United States must place the spirit of our First Amendment squarely above any business concern, political whim or bureaucratic expediency.

She had this to say, “If we want democracy to survive in the internet age, we really need to work to make sure that the internet evolves in a manner that is compatible with democracy." MacKinnon points to the insidious nature of the state’s use of the private sector to conduct its surveillance or censor its people’s social discourse. We in the United States must place the spirit of our First Amendment squarely above any business concern, political whim or bureaucratic expediency.

No comments:

Post a Comment